Imagine that you have just founded a company—you’re going to act as CEO and work on product and business decisions, and your technical cofounder is going to handle most of the building and design. You’re both fully committed and you’ve both quit your day jobs. You plan to hire some contractors and employees later but they will not be co-founders, so you decide to split your equity around 60% for your co-founder and 40% for you, and issue stock accordingly. As much as you and your co-founder trust each other, you want to make sure that you both stay for the long haul and put in the work needed.

Fortunately there is a process by which you can agree to "earn" your shares over a period of time, vesting, and you and your co-founder should almost certainly make your stock grants subject to it.

Vesting has two main benefits: it incentivizes a person to stay, and it protects the company in case the person leaves. From a mechanical perspective, here’s how vesting works:

What is vesting?

Vesting is the mechanism that allows founders and employees to earn their shares over a period of time. Although founders and employees can (and at times do) earn their shares based on certain actions (hitting $1M in sales, hiring 50 employees, etc), most vesting agreements are based on time, and so they are referred to as a vesting schedule. So:

Founder vesting is a schedule contingency on a stock grant which means that, over time, the company’s right to repurchase shares of stock decreases at a set rate of shares per timespan.

You and your co-founders will actually buy your shares on day one (usually at par, or $0.00001). However, your company will have the right to buy the shares back from you at $0.00001 if you leave the company. This is called the repurchase right. As time goes on, the company loses its right to buy back the shares, and the founders will own the shares outright and without a contingency. Effectively, the founder will "earn" the shares away from the company. This structure allows for better tax treatment (as the founders will own the shares from day one) and provides the company with some assurance that the founders will stick around for a long period of time.

In the case of options, vesting works slightly differently: an employee who has received an option grant subject to vesting is increasing the number of shares they are allowed to buy (or exercise) at any given moment, rather than decreasing the company’s right to repurchase shares they have. For the rest of this article, we’ll focus on our example co-founders and their stock grants to discuss vesting.

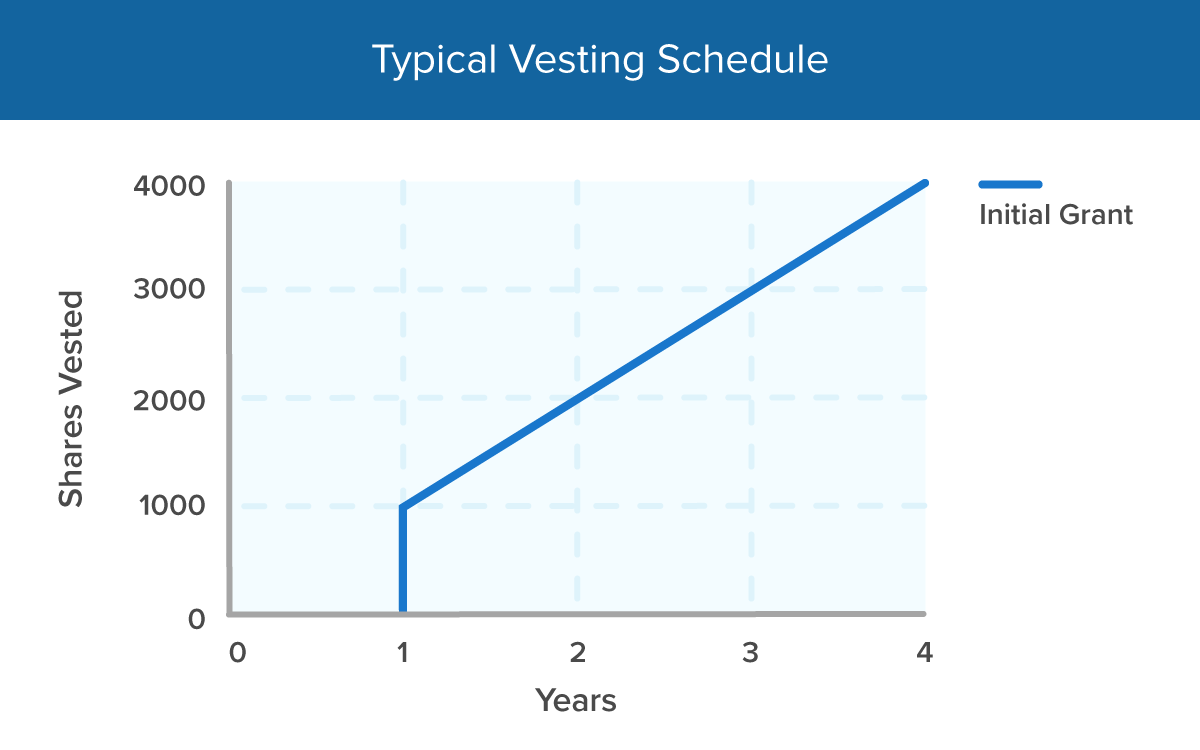

Typical vesting schedules and terms for startups

The most common vesting schedule for startup equity is over a four year period (48 months) where 1/48th of the founders share will vest and be released from the company's repurchase clause each month. To ensure that the founder will stick around for at least a year, no shares are actually vested during the first year; rather, the first year’s shares are all vested at once at the end of the first year. Effectively, they all vest after a "cliff." Then, the shares vest at a steady rate until the shareholder is fully vested. Thus, this schedule is: “four year vesting, one year cliff, monthly after the cliff."

The start of the schedule isn’t necessarily the same as the date of the stock grant. Some founders choose to set their vesting start date back before the incorporation, as a way of giving themselves credit for the work they’ve already done on the project. This is purely a matter of preference, but you should consider it in the context of vesting’s purpose overall.

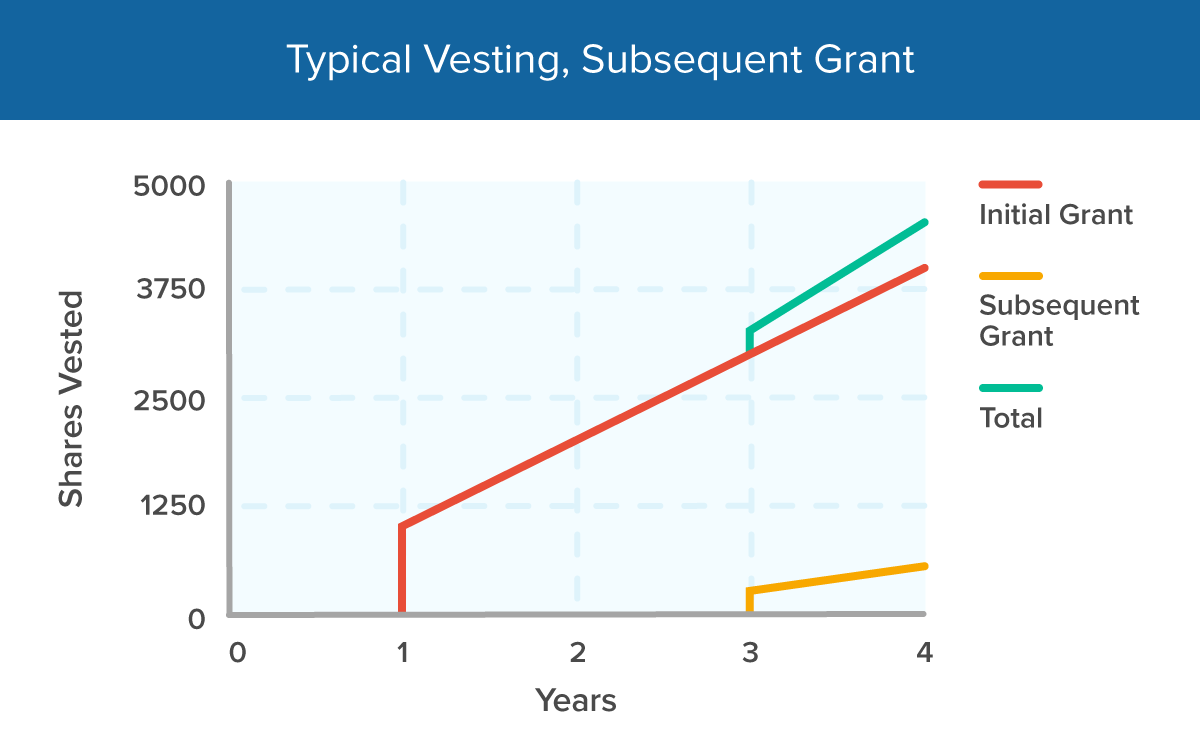

There are two other important things to know about how vesting works. The first is that vesting is a feature of the grant—the vesting schedule in stock grant only applies to that grant, not subsequent grants, and has no relationship to the length of the recipients tenure. So, if a founder receives a 4,000 share grant with 4-year vesting and a 1-year cliff, and then receives an additional 1,000 shares with the same schedule after two years, it looks like this:

The other key vesting feature to remember is acceleration, which comes in two common flavors: single-trigger or double-trigger. Basically, acceleration just explains what happens in the event that the company is acquired. In typical single-trigger acceleration, the acquisition causes all remaining unvested shares to vest immediately. Under double-trigger, the remaining shares vest all at once if two conditions are met: usually the two conditions are the acquisition of the company and the termination of the grantee, but they could be a variety of things. Acceleration is typically only used in equity grants to founders and executives.

Now that we know how vesting works, we can understand why you need it.

Reason 1: Vesting protects your company

The main reason to make a grant subject to vesting is really to protect the company. Although of course you would not be embarking on your startup’s journey with your co-founders unless you trusted them, people and situations can both change (and they often do). Without vesting, if things don't work out for one of you, one co-founder can walk away with their entire portion of the company, and the one who ends up staying will effectively be stuck building a company for their retired team member.

Part of the issue, of course, is that their equity would be a claim on any gains your company makes in the future. But equity isn’t just a share of the spoils—it also includes voting rights. If your technical co-founder in our example leaves with 60% equity, she’ll have decision-making power. That can hamstring your company’s operations, whether or not their parting was on friendly terms. And even if your co-founder had less than 50%, they’d still have a significant voice as a voter.

There’s a third kind of protection here, too: vesting helps you take care of your cap table from the very start, so it can be as clean and logical as possible when it’s time to raise investment. Investors care about shares and voting too (since they’ll be buying a large chunk of your company) but even beyond that, they’re interested in how you run your company.

Without vesting, you might have to explain why someone who briefly worked with you two years ago owns 40% of your company, and the investor will hear the explanation as a signal about whether or not you’re a competent, careful startup leader. Under a vesting schedule, that person would own none or maybe 10%, and you can explain that it didn’t work out but they were compensated for the work they put in. They left, the company repurchased their shares, and the investor doesn’t have to split the proceeds of their investment with someone who isn’t adding value to the venture.

Reason 2: Vesting helps incentivize team members

Vesting encourages team members to stick around when times are tough. Most startups must go through various crises and long hours on lean budgets. In these situations, having a growing stake in the company can be a compelling reason to stay on the team and keep working toward the goal.

This motivation rings just as true for employees as it does for co-founders, which is a big reason option plans are such a popular type of incentive for startups to offer. When a person is promised a share of something you’re working on, it makes the project more personally important to them, and makes other opportunities that much less attractive.

So in our scenario at the beginning of this article, the co-founders’ choice isn’t really about delaying the amount of time it takes for the shares to become “theirs.” What they’re really doing is deciding to put the company first and commit to working on the team for four years or more, and asking their co-founders to do the same.

In this context, it makes a lot more sense—vesting protects your company and your co-founders by aligning everyone’s stake in the venture with their commitment to it. For nearly everyone, that means vesting, including for founder equity, is the right way to go.

Learn how to pick the right startup legal entity:

This article is intended for informational purposes only, and doesn't constitute tax, accounting, or legal advice. Everyone's situation is different! For advice in light of your unique circumstances, consult a tax advisor, accountant, or lawyer.